(For Part 1, see here; for Part 2, see here.)

Some years ago I wrote a post asking if Battlestar Galactica was too religious. To this day it remains one of my most popular pieces. Controversial, too. Not because of the meat of the post itself but because some people just don’t like religion. At all.

But let’s put aside whether or not religion is good or bad or whatever. Let’s instead focus on religion in Battlestar Galactica. After rewatching the entire series I can say with 100% confidence that one of the major themes of the series was in fact religion. Not just religion, but God and our place in the universe.

In my opinion, Battlestar Galactica was one of the most overtly philosophical television shows of this century.

In the series we had two separate camps when it came to religion. First were the 12 colonies, each named after a zodiac sign (astrology—a quasi religion in my view). The colonists paid reverence to the gods. Not a single god but a collection, patterned off of the Roman gods. Devotions, sacrifices, all of that.

One of the most religious characters among this religion was President Laura Roslin. I can’t say for sure what her level of faith was before the events in the story, but when we meet her, she’s just been diagnosed with terminal cancer. She turns to the gods and takes solace in the scrolls of Pythia, which foretell of a dying leader who will take her people to safety. She’s beset by dreams and visions (drug induced?) that she takes for messages from the gods. Her faith, whether or not conditional, is in the forefront of the storytelling.

And then we have the cylons. The Caprica who appears to Gaius Baltar talks of one true God, a God who had a plan for everyone. It’s obvious what the writers were doing here: contrasting a pagan faith of offerings and visions against the Judeo-Christian singular God who had an individual connection with each of his creations (children).

The show ping-pongs between these two world views. It also provides an interesting commentary. For both camps, the colonists and the cylons, their religions/faiths don’t necessarily make them better or more virtuous. If anything, they use their religions to justify their actions. It’s pretty convenient that at first, the cylons view killing billions of colonists as part of God’s plan.

That’s a pretty dark view of religion.

But Battlestar Galactica is suffused with religion, with belief, with gods or God, and that’s part of what makes the show so interesting, even 20 years on.

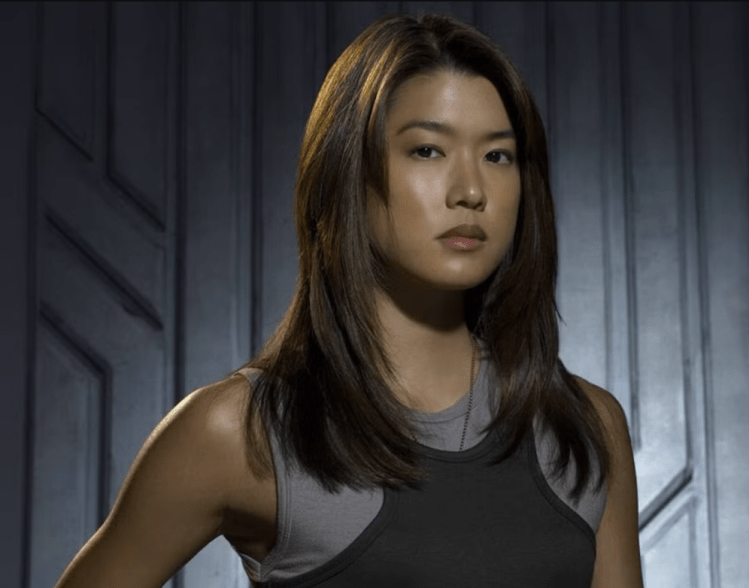

The second major theme of the series is one that’s become a sci-fi trope: what is the definition of personhood? Are the cylons persons? In the series this question arises with the twelve humanoid-looking models. And no character best represents this than Sharon.

There were two significant Sharons in Battlestar Galactica. The first was Boomer, an ace fighter pilot in the Galactica. What Boomer did not know was that she was a sleeper agent. She believed she was human. She’d had memories implanted. She was in love with Galen Tyron (who turned out to be a sleeper cylon himself, though not one of the baddies). Then she was activated and shot Adama, nearly killing him. The series portrays her struggles to retain her humanity even as she loses her world.

Then there’s Athena, the other Sharon. On the cylon-controlled Caprica, this one pretended to be Boomer in order to trick a stranded Karl Agathon. She always knew just what she was. But somewhere along the way she fell in love with Agathon. They return to the Galactica and she dedicates herself to fighting her fellow cylons, along with having a daughter, Hera, the first human/cylon hybrid.

The series made a strong case for the humanity of both these Sharons. And there were other models thrown in there too. When colonists brutalize one of the Sixes, for instance, who’s the monster? On the flip side, let’s go back to the miniseries, when Caprica snaps the neck of a baby. Monstrous. Inhuman. But…she changes and grows and eventually leads a faction of cylons to seek another path with the colonists.

There’s a third major theme of Battlestar Galactica, and in my view, it’s the weakest. Keep in mind when the series first aired: 2004-2009. America was coming off 1) a major terror attack, 2) paranoia about sleeper agents, 3) critiques of blowback from decades of botched foreign policy, and 4) not-successful invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq.

At the time I remember reading commentary stating outright that the series was a response to the GWOT, and if you look closely at the storylines you can definitely see it. We’ve got an angry foe seeing revenge, a clash of civilizations, rampant terrorism, sleepers (cylons), and then the cylon occupation of New Caprica (one of the weaker storylines). We’ve also got brutality and torture galore.

As a larger commentary on American society of the zeroes, this comparison leaves me kind of flat. Don’t get me wrong, within the confines of the show, this all worked. But maybe I’d just not rather relive those dark days.

Next up: the hits.