The challenge: write a complete story in 500 words or less following these guidelines:

Setting: An operating room

Genre: Amish romance + Medical mystery

Trope: Decoding ancient texts

Characters: Acrophobic five-year-old math genius + Martian

POV: 2nd/future

The result:

Oddity

You’ll record these moments in your mind. You’ll transcribe them. For her. For posterity.

The boy will sit with his ankles crossed and dangling, refusing to look your way. “We’re 72,000 feet from the surface,” he’ll say. “If I plummet through that window it will take me 8.7 minutes to crash. My body will splatter in a diameter of 1.28 miles.”

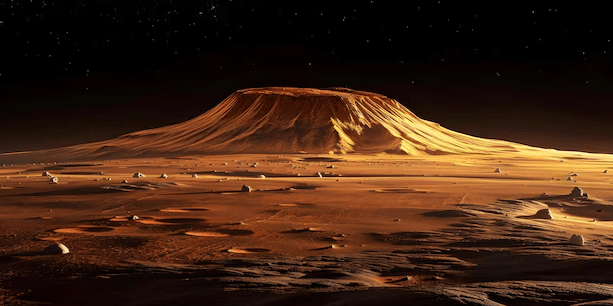

With all the current strife, this laboratory on the peak of Olympus Mons is the safest place on Mars. Sometimes you forget he’s only five: frail and pale with wild hair. “I see. You’re afraid of heights. How about you turn your back to the window?”

He’ll comply and as he begins to swing his legs you bring forth the rune. He runs his fingers over it. “It’s not a forgery,” he’ll say. “These carvings resemble those on the Xanthe cave tablets.”

“Yes, Abigail found those stones.”

“Tell me about her again.”

You’ll sigh and stare out the window. You can almost see all the way to Drava Valles from here. You and Abigail were children when you met, seventh generation Amish colonists. You knew instantly you were fated to be together. You courted and pledged yourselves to each other, and when you both turned seventeen, you married. That first kiss was an electric shock. You can still feel it reverberate. “She was the most brilliant person I’ve ever met. And the most beautiful.”

“Sounds too good to be true,” the boy says, suddenly sounding too wise for his years.

“Isn’t every romance story?” You’ll glance over at the operating table. Empty. How much blood has pooled on this floor? You can’t think about that now. “Her life’s work was solving the mystery of the Xanthe tablet. And now with this rune we’ve discovered…there has to be a connection.”

“And you think it’s me?” the boy will ask.

Innocently. Too innocently. The first child genius was born nine months after the tablet was unearthed. This boy is the seventh. “Ever since we’ve found this proof that we’re not alone, there’s been so much turmoil. We have to know what they say.”

He’ll squint at the tablet, then the rune. “These markings form a code.”

“Can you decipher it?”

“Close enough, yes. It says, After one thousand years the soil makes them ours.”

A shiver will crawl down your spine. “We’ve been on Mars for nearly a millennia.”

“There’s more,” he’ll say. “Two in the blood will become three.”

“What blood?” you’ll ask.

He’ll look at you so mournfully that you’ll forget about his unnatural intellect and see him just as a child. The skin of his arm is so white, and in his silence you’ll find the answer. You won’t ask his

permission to draw his blood. He won’t resist. Under the microscope you’ll magnify until you hit his DNA. And then you’ll see it: not two strands entwined but three.

You’ll stare at this impossible Martian child, all the time wishing Abigail was here to witness this glory.