(For Part 1 in this series on the Battlestar Galactica reboot, click here)

When I was a kid I hated Jimmy Carter for one reason: he got the Israelis and the Egyptians to sign a peace deal, and the televised signing of that peace deal interrupted the 1978 premiere of the original Battlestar Galactica. I still haven’t forgiven him for this.

The first incarnation of Battlestar Galactica, created by Glen A. Larsen, lasted just one season with 24 episodes. There was a short-lived resurrection called Battlestar 80 that expired after ten episodes. I forget a lot of the details of Battlestar 80 but reading the synopsis it sounds like the writers were heavily into whiskey and cocaine.

I won’t get into how the original compares to the reboot overall. I don’t think that’s a fair comparison for a couple of reasons. First, television technology—special effects specifically—has improved vastly over the quarter century between the two shows. Second, although they’re essentially the same stories with a bunch of the same characters, they’re from different writers who had different visions.

Also, I’m not going to go through a detailed list of the differences. But there are three differences I want to highlight.

The first, in the scheme of things, is relatively minor.

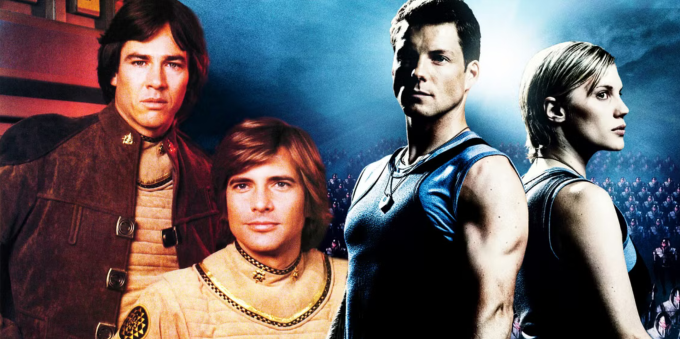

Seven-year-old me wanted to be the ace fighter pilot Starbuck. Played by Dirk Benedict, he was brash and wisecracking and cigar chomping and a good time. When news of the reboot came out, I learned that Starbuck was getting a sex change. He’d now be a woman, played by a woman (Katee Sackhoff). Seven-year-old me was not happy. Adult me considered it a cheap PC stunt. Nowadays sex-swapping characters is so commonplace it’s almost a cliché, if not a joke. But back then I can’t recall it happening all that much.

So, yes a stunt. Yes, odd. Yes, annoying. But…

…thanks to the writing and Sackhoff’s portrayal, it worked. Kara Thrace, aka Starbuck, was gritty and brash and complex and messy and fun, and while, in my opinion she could have remained a he (we didn’t really need that forced romance between her and Apollo), Sackhoff helped make the show what it was.

The second difference between the two series was a major change. In retrospect it seems like such an obvious idea I’m surprised it wasn’t in the original. In the original, the cylons were these hulking and bulky metallic toaster-looking robots.

The reboot had these steel cylons in spades, plus another type of cylon, a type that looked human, 12 models with many copies, to be exact, models with different personalities, and the reboot introduced yet another twist: some of these humanoid cylons didn’t even know they weren’t truly human.

This opened up a universe of tension. Who is a cylon and who isn’t? Who is a sleeper agent? Are cylons redeemable? Do they have a sense of self? A soul? All these questions are great plot fodder, and they’d be much harder to pull off with robots that look like toasters.

Another major change had to do with tone. Seventies sci-fi in general was fun and colorful, unintentionally campy even when trying to be serious. And the special effects were definitely underwhelming. The original fit this profile.

The reboot, in contrast, was darker. Literally. Early episodes employed the shaky camera technique that was trendy back in the zeroes (I hate it).

The tone was darker, too. It had a sheen of noir, which totally fit a series about the nearly total holocaust of the human race. No, you can’t necessarily call a show about robots massacring humans lighthearted, but compared to the original, the reboot went a thousand times darker. Torture of all kinds. Lots of violence. Lots of sex (censored). Humanoid cylons acting monstrous and humans acting monstrous.

It might all sound too heavy, but this is a heavy premise. Taking out the camp and throwing it away worked.

Next up, a look at the major themes of the Battlestar Galactica reboot.